I have been in many art museums and galleries over the years. Few compare to the Museo del Prado in Madrid for grandeur and sheer volume of work. If you should ever desire to have too much of beauty, too much magnificence, then the Prado is the place for you. Go there and gorge yourself upon roughly a thousand years’ worth of the art of the Western world, exhaust your eyes upon those massive canvases and panels filled with the glowing faces, hands, and breasts of silk-robed contessas and duchesses, and brocaded noblemen staring down haughtily at you from atop their gleaming, thick horses. Or, if you are weak in your knowledge of biblical lore, having been as much a Sunday-School slacker as I was, then works by Ribera, El Greco, Velazquez, and many others will bring those hoary characters to life for you once again; you will see the violence of Samson and the grisliest sufferings of Christ in images that would have been deemed unsuitable for The Children’s Book of Bible Studies.

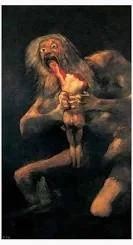

I was there my first time in 1985, and I remember walking through those myriad rooms in a kind of daze. It was a lot for a foolish young man to try and absorb. I recall looking at picture after picture by the great Francisco Goya, reveling in the velvet glories and rustic history of Spain. But one painting stood out in my recollection over the years: it was his depiction of the Roman god Saturn devouring one of his sons. Yes, I do mean eating him alive, having already bitten off the boy’s head, the crouched Saturn with blood streaming down his bearded chin and utter depravity in his bulging eyes. Apparently he feared that one of his offspring would usurp him, and so he sought to destroy them all (one survived, of course, so his precautionary measures were all for nought). The painting is appalling, and it did not seem to me to accord with the museum’s overall themes of elegance and drama, both human and divine. I turned away from it with suppressed horror.

I was not aware at the time that the Saturn painting is one of fourteen attributed to Goya that are very different from most of his work. They are called the Black Paintings because they are quite dark, mostly monochromatic in shades of gray and varying depths of black. They also portray a blackness in the soul of the artist, and they derive from that abyss that exists in us all; we cannot even call it hopelessness or sorrow - it is farther down than that, in that place in us where nothingness (and not merely the fear of nothingness) abides. It is no wonder that, at age twenty-seven, I could not look at them; I was in no way prepared for such blunt truth.

Nearly thirty-eight years later, my perspective has changed. Just a few days ago, in the lower level of the Prado, I came eye to eye with Saturn again, along with the strange figures and haunting faces and the darkness of the other thirteen works. In lurid fascination, I looked upon those leering, perverse men and women of eternal twilight, their gaping, toothless mouths and shadowy eyes rendered in fat, black strokes. One, simply called Dog (Goya himself did not give titles to these paintings), shows a dog’s head in its lower left quadrant, but the viewer cannot quite tell whether the animal is just emerging from behind what appears to be a hill in the foreground. or whether the head is simply lying there, freshly severed. The rest of the picture is a long, empty stretch of dirty brown and gray hues with no light or shadow. The work constitutes a wordless definition of acute loneliness.

If some patrons find these pictures disturbing today, imagine how Goya’s admirers and contemporaries might have reacted. Let’s examine another piece from this small collection, called Witches’ Sabbath. In the foreground, a demonic he-goat leads a group of followers in s smoky ritual. His back is to us, and his congregation is comprised of craven, raven-headed worshippers whose faces are twisted by both decay and carnal pleasure. In my experience, Christians - and especially Catholics - have always been poised to do battle with the Enemy; the night watch is always en garde, as it were. Yet this rendering somehow repulses and invites; we are simultaneously drawn in and horrified. This is not St. George skewering a dragon from the heavenly heights of his white steed’s back. Who, among the vast majority of us who have not attended such a forbidden ceremony, has not wondered what actually goes on? Oh, by the way, your soul might be at stake, but even the brilliant Faustus was ultimately pulled under by his demons, wasn’t he?

Perhaps in part, this explains why the Black Paintings were virtually unseen and unknown during Goya’s career. The provenance says that they were done late in the artist’s lifetime, around 1822, when he was in his mid-seventies, following a ravaging illness, the onset of deafness, and during a steady mental decline. He painted them on the walls of his house near Madrid, and they were not produced under contract (as was the case with much of his work), nor were they ever sold. In 1874, fifty-one years after the artist’s death, they were finally removed and transferred to canvas. Today some say that this haphazard, almost incidental uncovering marks the beginning of modern art.

The paintings represent such a drastic departure from Goya’s other attributed works that some art historians have concluded that he could not have painted them. One of those experts, Juan Jose Junquera of Complutense University in Madrid, further argued that the pictures were likely created by the artist’s untrained son, Javier, since the house in Salamanca was only one level when the artist died, though other documents indicate that the images were found in rooms on a second story. (https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-paintings.html)

It is the sort of dilemma that sometimes arises when we attempt to understand the nature and temperaments of highly creative people. For instance, the skeptic says: There is no way in heaven, hell, or on earth that a country bumpkin from a small English village could possibly have written the towering works attributed to William Shakespeare. Oh, and there can be no doubt that Branwell Bronte - not his cloistered sister Emily - must have written Wuthering Heights, since no woman could possibly have imagined the sort of viciousness as is shown in that book. Similarly, Percey Shelley must have ‘ghost’ written the novel Frankenstein, for sweet little Mary Godwin could never have been the progenitor of such a remarkable and shocking story. We who are not creative geniuses do not begin to understand those who are, plain and simple, so we are disinclined to believe in a true, dynamic masterpiece of art even when we see it. It is not simply that some artists are smarter than we are: no, the truth is the path of creativity is often unpredictable, it goes where it will, and in fact, it never rests. It is like letting go of a steering wheel - maybe you will crash, but if you don’t, you will be forever touched by a sense of the miraculous.

The human imagination remains mysterious, and it is often in defiance of logic and what we may call ‘predictability,’ and it occasionally takes us into places we would rather not visit - and yet they exist nonetheless. This is why my own conclusion is that Francisco Goya, the same man who was commissioned to paint the families of kings in their white stockings and gold-layered dresses, also painted the Black Paintings.