Everywhere I have been in Spain, I have seen and heard guitars. Mostly they’ve been classical-style, nylon-string guitars, with that sound that can be like a throbbing heartbeat or like the soft steps of a ballerina’s feet as she races across the stage, leaps, slows down, and then races away again. In the hands of a master player, the music can be as intricate and thoughtful as a great poem; even in the hands of a lesser player, it can draw you in quick and deeply.

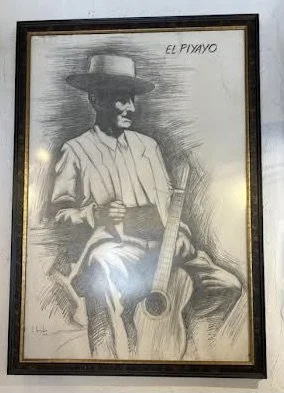

If you were a tourist in southern Spain, as I am at the moment, you would no doubt go to a cafe or a taperia on a sunny day, and soon, a guitarist would appear from around a near corner, carrying his instrument under one arm just as he has done almost all of his days and nights, and he will settle himself a few feet from your table and begin to play, whether you like it or not. The waiter and others connected to the establishment will not shoo him off, as they probably would at an American sidewalk cafe. They do not pay him any mind at all; he is merely a fact of life. He sings to you, and although his voice might be somewhat ragged and his pitch, at times, subjective, if you listen with an open heart, you will hear things in his singing and playing that you already know. You had no idea that you knew them, but you do: the smell and color of the brown earth, the scent of strong cigars, the timbre of black coffee in a small cup…

It’s what we in America call folk music. Put simply, it is a spontaneous exchange between the musician and the listener. Preferably, the performer must not have too much in the way of strict training, since this kind of music has always defied the rules anyway, just like all great popular art forms.

When he has finished his song, the guitarist will approach your table and smile broadly as he turns his guitar over so that the back of it becomes a makeshift portable table. This is so that you can place a coin on it, and even if you put down only one euro, he will receive it with the same grace and appreciation as though it were a thousand euros, for he is not a beggar - he is a guitar player.

Remember that such a person has a story, too. Maybe he learned a few chords from his grandfather long ago, enough to build a brief repertoire of songs to earn his pittance for the day; or maybe he was talented and aspired to be a composer or player of renown, like Francisco Tarrega or Josefina Robledo or the great Segovia, but something got in his way. In any case, he deserves at least a coin or two for his efforts.

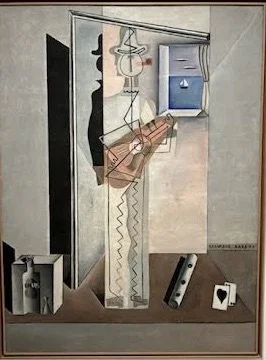

Any of us who plays the guitar (as I do and have done since I was fourteen) and anyone else who simply appreciates guitar music owes a significant debt to the Spanish. Its Islamic past in particular, has contributed greatly to the rise of the guitar as a force in musical history, in a wide range of genres. Generally and over time, an interesting pattern has emerged: poor people have often played music for rich people in order to earn a living, and sometimes their gifts have been such that they have ended up earning a very good living. So it should come as no surprise that it was a North African slave named Zyryab who laid the foundation for what would become the Spanish musical tradition, and in turn for much of the music of the West, both popular and classical. A brilliant man of the arts, he played a middle eastern stringed instrument called an oud, and in the early ninth century, he started a music school in Cordoba. Over the ensuing decades and centuries, expanding trade and population shifts brought many other early variations on the idea of the guitar - among them the vihuela, the baroque guitar, and the more familiar lute. Continuing conquest and trade took the guitar to Latin American and North America. Ultimately, the guitar appeared in the Mississippi Delta and in the Piedmont region of the southern U.S., where it was inevitably again integrated into the music of various cultures, thus creating what we now call American traditional music. What happened after that has probably been best articulated by the great bluesman McKinley Morganfield (a.k.a. Muddy Waters): “The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock ’n’ Roll.”

Speaking for myself, I have had no formal training on guitar. In my playing, I’ve done what many “folk” players do, and have simply followed my own ear into different kinds of music that appeal to me: blues, bluegrass, old-time fiddle music… But one of the best things about playing in those styles is noting the ways in which they overlap with one another while also absorbing ideas from the most unlikely of sources. Listen to some of bluegrass mandolinist David Grisman’s “dawg” music from the 1980s, for example, and you’ll hear elements of jazz, classical music, gypsy music, and…flamenco. No question about it.

Typically, any player from Spain will be well-versed in Andalusian flamenco music, but he or she may have studied classical guitar as well, since the two styles are close cousins. In fact, some musicologists contend that at one point in the guitar’s history, they were likely indistinguishable. As they gradually diverged, though, flamenco guitar came to be regarded primarily as an accompanying instrument for one or more dancers, whereas classical guitar compositions and arrangements of pieces by artists such as Bach and Chopin - as well as Spanish composers, of course - are intended to be played on a concert stage. Once again, it was the influential Zyryab who, centuries earlier, had understood both the distinctiveness and the potential confluence of various musical cultures and instruments.

That is one of the many reasons why, when I hear a native Spaniard playing a guitar in the Spanish way, I pay attention. And I nearly always feel something, and that part I can’t really help. It is something difficult to identify or describe, and it speaks of a past which is both mysterious and cavernous, like a moorish castle, and as exhilarating as the wind that surges along the Mediterranean coastline. It is about mournful harmonies and the deaths of lovers. The exact words elude me, so here is something that Andres Segovia said:

“Among God’s creatures two, the dog and the guitar, have taken all the sizes and all the shapes, in order not to be separated from the man.”

Some of the information for this blog came from online.berklee.edu.